ORGANISTRUM : ITS TUNING AND KEYBOARD.

The aim of the present article is to present the ultimate result of my research on the possibility of rebuilding the Organistrum.

Please read my article on-line: https://ojs.unito.it/index.php/archeologiesperimentali/article/view/8489

see also: Giuseppe Antonio Severini, Organistrum. Un caso di archeologia sperimentale. Tipheret, 2020. Italian text only.

1.Sources and features

The information we have on the instrument comes from a dozen images in books and works of art of the 12th century.

Constant elements

- The Organistrum has an « 8 » shape, with a rectangular extension.

- The dimensions are such as to occupy the knees of two men seated side by side.

- The wheel and the crank are a characteristic element, as are the three strings, in one case two, in one other perhaps one.

- The row of keys ends within the middle of the string.

Variable elements

The number of keys can change: 6 to 11 (or 12).

Unknown elements

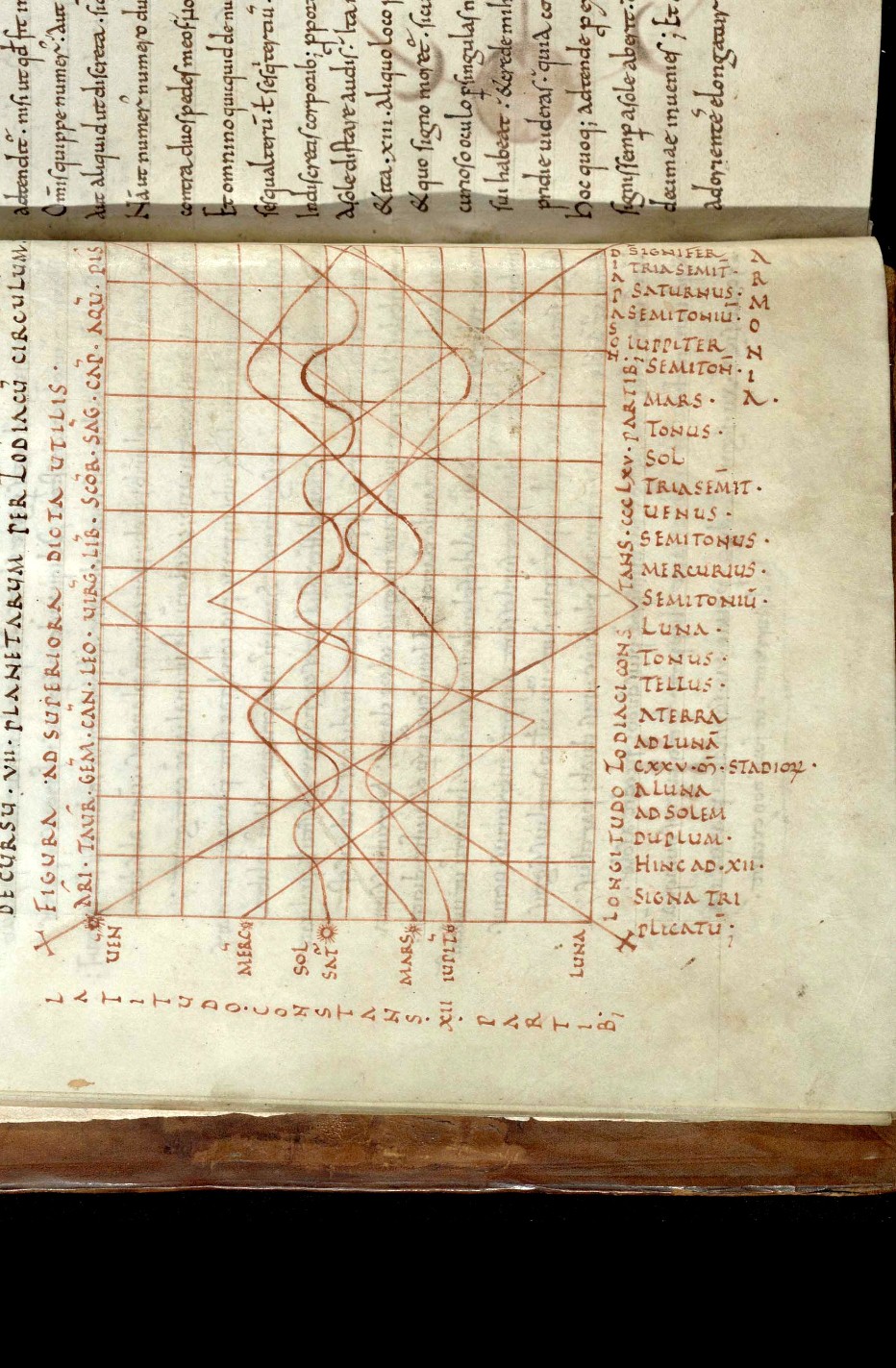

I. There is no information about the tuning and the musical scale but from a plate in Martin Gerbert, De cantu et musica sacra, 1774. The same drawing gives an idea of the possible mechanism of the keys.

II. We know nothing more about the inner structure of the keyboard.

From these premises it follows that the replicas of the Organistrum so far attempted are at least partly hypothetical.

This obviously concerns the Variable elements and the Unknown Elements.

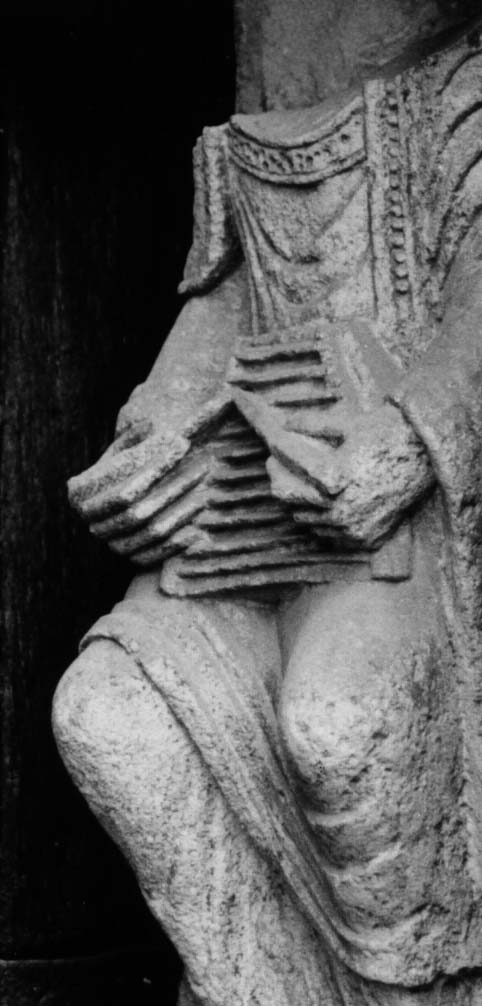

Almost all the replicas take as a model the Organistrum of the Portico de la Gloria of Santiago de Compostela because, compared to all the other representations it is the richest in details, it has the maximum number of keys, it occupies the most important location.

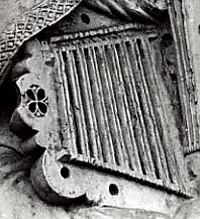

There are 12 keys within the octave, the first of which should be the nut : they are definetly too many, unless you want to conclude that this is a chromatic keyboard.

Another arbitrary element lies in the choice of the generally adopted fifth and octave tuning, inspired by the organum parallelum polyphonic technique, described in texts that precede any known depiction of the Organistrum by at least a century or two. Instruments made following these hypotheses have little use in the performance of medieval music.

2. A different solution

In search of a different solution, I found myself reconsidering two objects that are certainly of the first level.

A.) The only drawing of the keyboard that we have left, complete with indications on the scale and on the structure of the keys, is the one copied by Martin Gerbert from a 12th c. manuscript, now lost, in Saint Blaise monastery.

Gerbert's keys have been interpreted as revolving bars with a long "spatula" tangent placed under the strings. The tangent would be brought into contact with all three strings simultaneously through a rotation. This system does not work in practice.

I prefer another interpretation of this drawing: the eight keys would be rotatable or lever acting from above the strings, pressing them against fixed frets, and it works.

Gerbert provides a scale for the instrument: from C to the next C with a single accidental, Bb. The fact that the intonations of the other two strings are not indicated leads to the conclusion that :

- they all had the same frequency;

- were in C with different octaves;

- Gerbert has forgotten to copy them.

The indicated scale is the canonical one and logically must be respected. The indication for the tuning being incomplete, this does not mean that it should be overridden. It is preferable to stick to hypotheses 1. and 2.

So we are faced with a diatonic instrument capable of producing all the intervals of the diatonic scale with a continuous sound. As several authors have observed, it seems to be an evolution of the Monochord. What could this instrument be used for? To provide a certain reference of the notes (a tuner), to play pedals in polyphony helping the singers in intonation.

B.) The musical repertoire coeval with the representations of the Organistrum, all of the 12th century, gives us more suggestions.

The manuscripts of Limoges, Winchester, Santiago de Compostela and Paris (Notre Dame), show an interesting two parts polyphonic repertoire. The scales are strictly diatonic. The only alteration used is Bb. These compositions were sung and intended for the liturgy. Many of these, called organum floridum or melismaticum, consisted of a bass vox principalis, and a higher vox organalis. Each note of the vox principalis corresponds to groups of many notes of the vox organalis. The extension of the vox principalis in the Magnus Liber organi of Notre Dame is mostly from C3 to D4, rarely up to F4. The compositions in the F key start at A2 and jump to C3, never requiring B2 and Bb2.

It is possible that the Organistrum as described by Gerbert effectively entered into the performance of these parts.

3.More than eight keys.

How should we consider keyboards with more than eight keys?

They are actually only two:

- organistrum from Collegiata de Toro (Spain) : the nut + 9 keys ;

- the one from Santiago de Compostela : the nut + 11 keys.

I think the most realistic keyboard is that of Toro, which only adds one tone (D) to the octave.

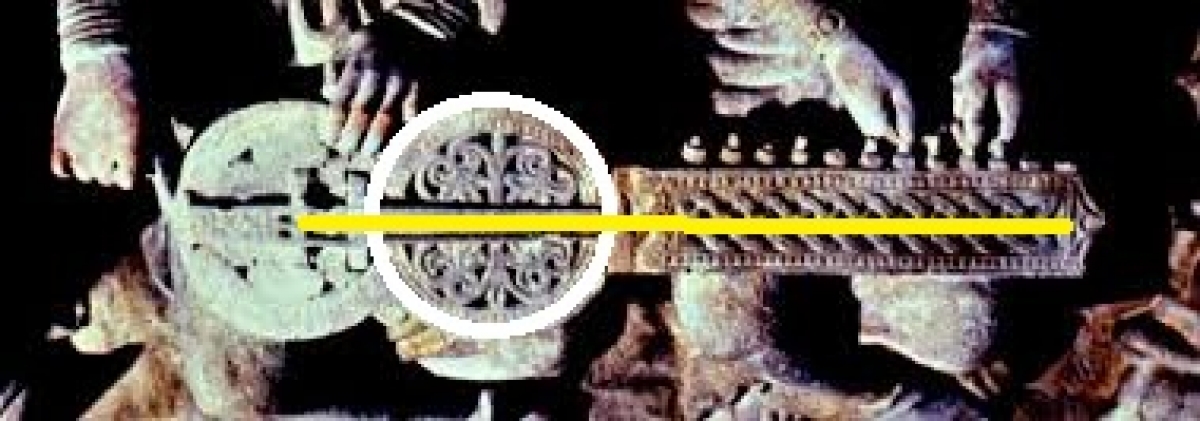

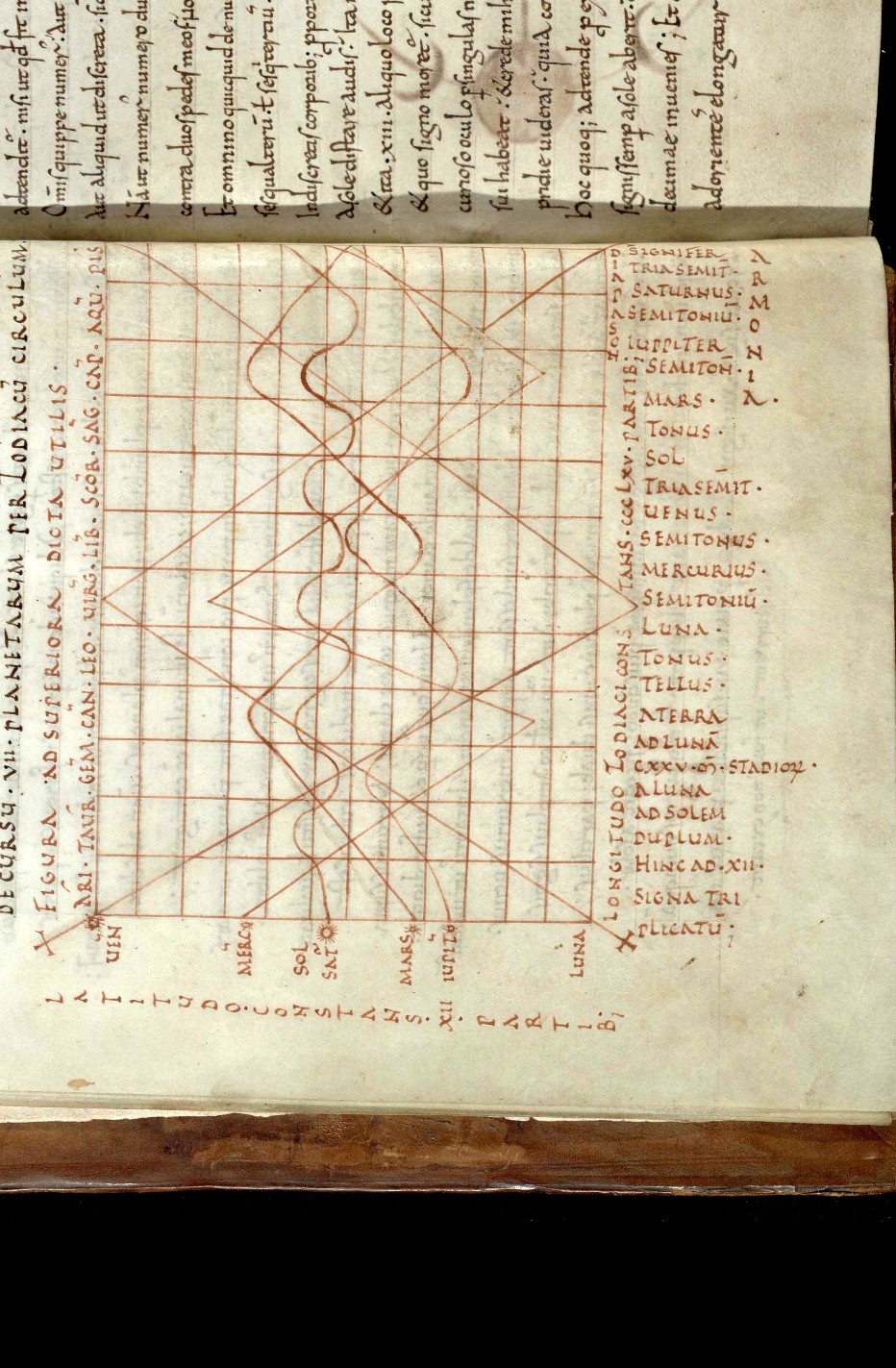

In the case of Compostela it is very difficult to think of an extension of the diatonic keyboard by two tones and a semitone without visibly exceeding half of the diapason. The Santiago instrument, certainly the most beautiful, has preponderant symbolic value, as amply shown in my book. The 12 keys do not want to indicate the intervals of the scale of the instrument, but those of the cosmic harmony according to Pliny, as can be seen listed next to many grids of planetary latitudes in 11th and 12th century manuscripts of astronomical content.

Plinian Harmonia besides Planetary latitudes graph from Trinity College Cambridge, ms R15.32, p.6

The setting of the instrument at the center and at the top of the Portico describing the Glory of Heaven, the decorative details and the fundamental measures of the instrument have an evident astronomical and theological inspiration. It's important to underline that this sculpture, belonging to a masterpiece of the highest level, as one of the three most important sanctuaries of Christianity, deserved great symbolic significance.

4.Acoustic results

As with all theories, a crucial aspect lies in the experimental verification.

I have listened to many instruments, others I have heard in recordings, I built four different types myself. My conclusion is that the most coherent and most convincing version, with the most pleasant sound, is the one with the three strings in C3 and a diatonic fingerboard with levers acting over the strings.

Watch this video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n2mqa5iZYFA

Best source:

https://ojs.unito.it/index.php/archeologiesperimentali/article/view/8489