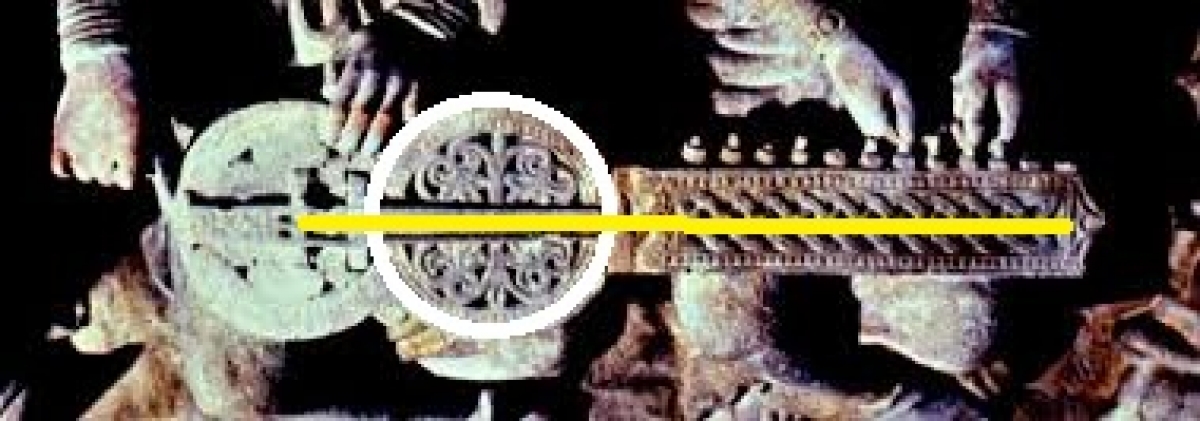

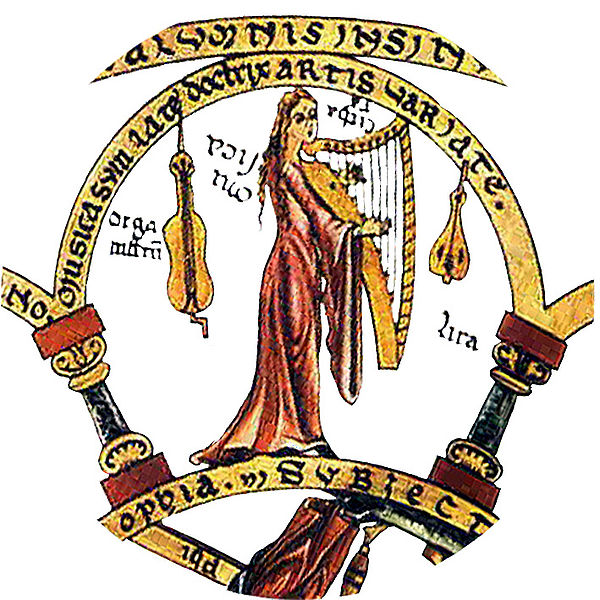

The Organistrum is always depicted in instrumental groups either related to the parade of King David (Old Testament) or to the group of the 24 elders of the Apocalypse (New Testament). The characters are in full robes, except for one of the two musicians from the Hunterian psalter (the one in charge of the crank, may be a servant). In the latter representation, in the capital of Boscherville and in the sculpture of Compostela, the musician who acts on the keys seems to have his mouth ajar, as if mid-song.

It is necessary to carefully analyze the few documents at our disposal in order to obtain as much information as possible.

Before I introduce this new phase of my research, however, let us recall the thoughts of two authors who had the same intuition about the function of Organistrum.

Francis W. Galpin in Old english instruments of music, 1910, states:

"The Organistrum, for such was its name at first, is undoubtedly derived from the Monochord, a simple contrivance for ascertaining the intervals of the musical scale by a series of movable bridges".

Laura de Castellet in: The sound space: Thought, Music and Liturgy, in the volume: Spaces of Knowledge: Four Dimensions of Medieval Thought, Barcelona, 2014, writes:

“At any rate, the Organistrum was not conceived as a relative or a surrogate of the organ for the embellishment of sound within the temple. For instance, the presence of an organistrum amidst the twentyfour elders of the Apocalypse of the Gate of Glory … and at the collegiate church at Toro (Zamora), does not mean that such instrument leads any kind of concert, but that it symbolically represents the study of the language of sound, mathematical speculation, and cosmological order, and the approach to the divine essence. The elders are not making music, but rather preparing themselves - some of them are tuning their instruments- both intellectually and spiritually to face the advent of a new order of things. » p.39.

According to both scholars, the Organistrum finds its origins from an instrument used to measure the pitch of sounds since ancient times.

However, in order to seriously consider the possibility that it played a significant role in musical practice too, it is necessary to identify its possible scope of use.

THE MUSIC

The context in which the instrument is described or depicted is always, and only, that of sacred music.

When it was still believed that the Organistrum had first appeared in the 9th century, it seemed to some to find an indirect reference within the treatise Musica enchiriadis.

The anonymous author meticulously describes a polyphonic practice called Organum parallelum. He states that the use of instruments was allowed in polyphony, so long as these strictly respected the voice pitches (Pia,2011). This encouraged some researchers to attribute to the Organistrum the role of Organum parallelum performer. They stated that two strings were tuned an octave apart and the third had to be tuned to the fourth or fifth (e.g. C3 – F3 /G3 – C4) (Rault, 1985). In other instruments one string is tuned to a fundamental pitch, the other two a fifth above (Kurt Reichmann). When operating a key all three strings are shortened.

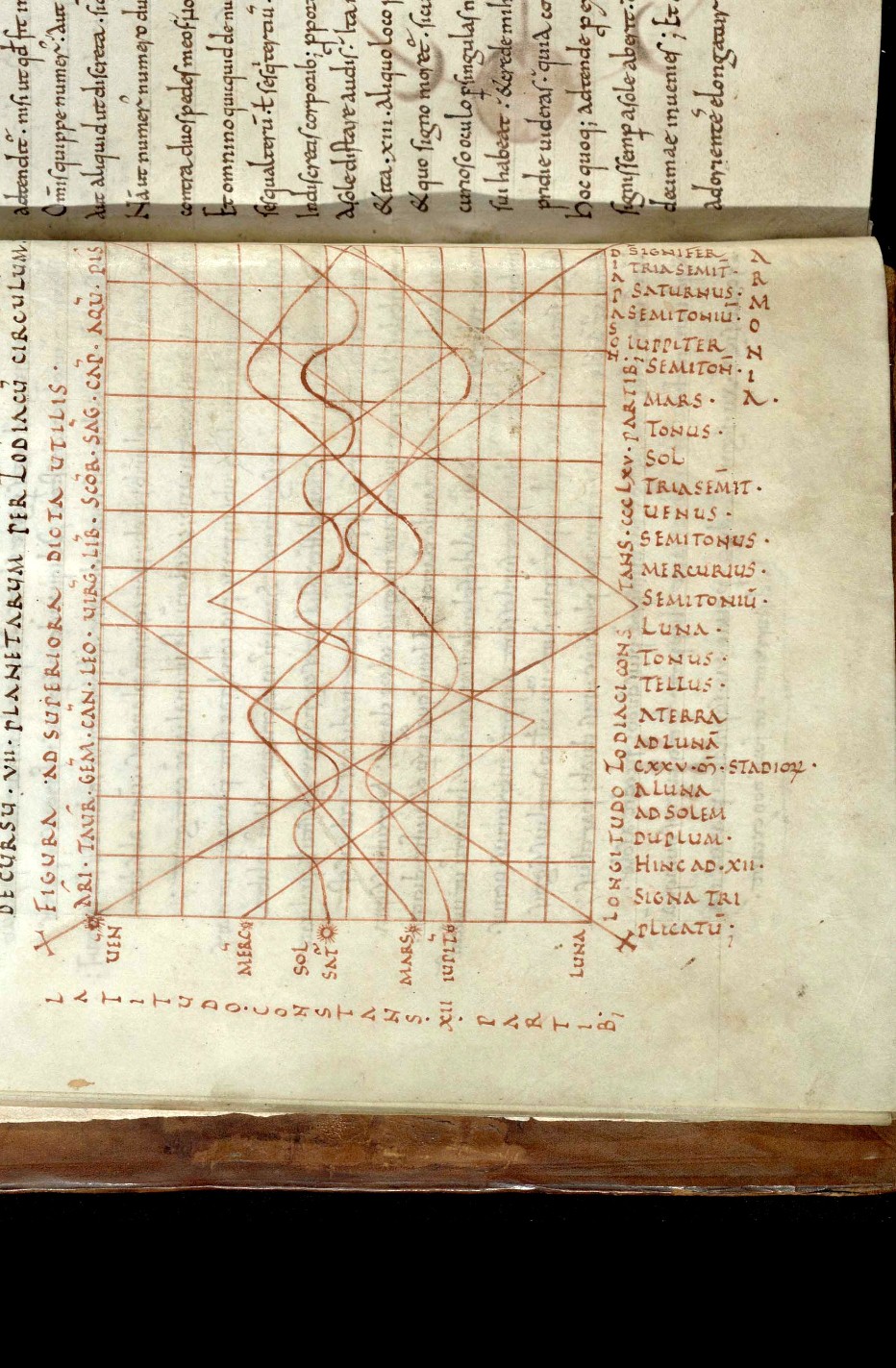

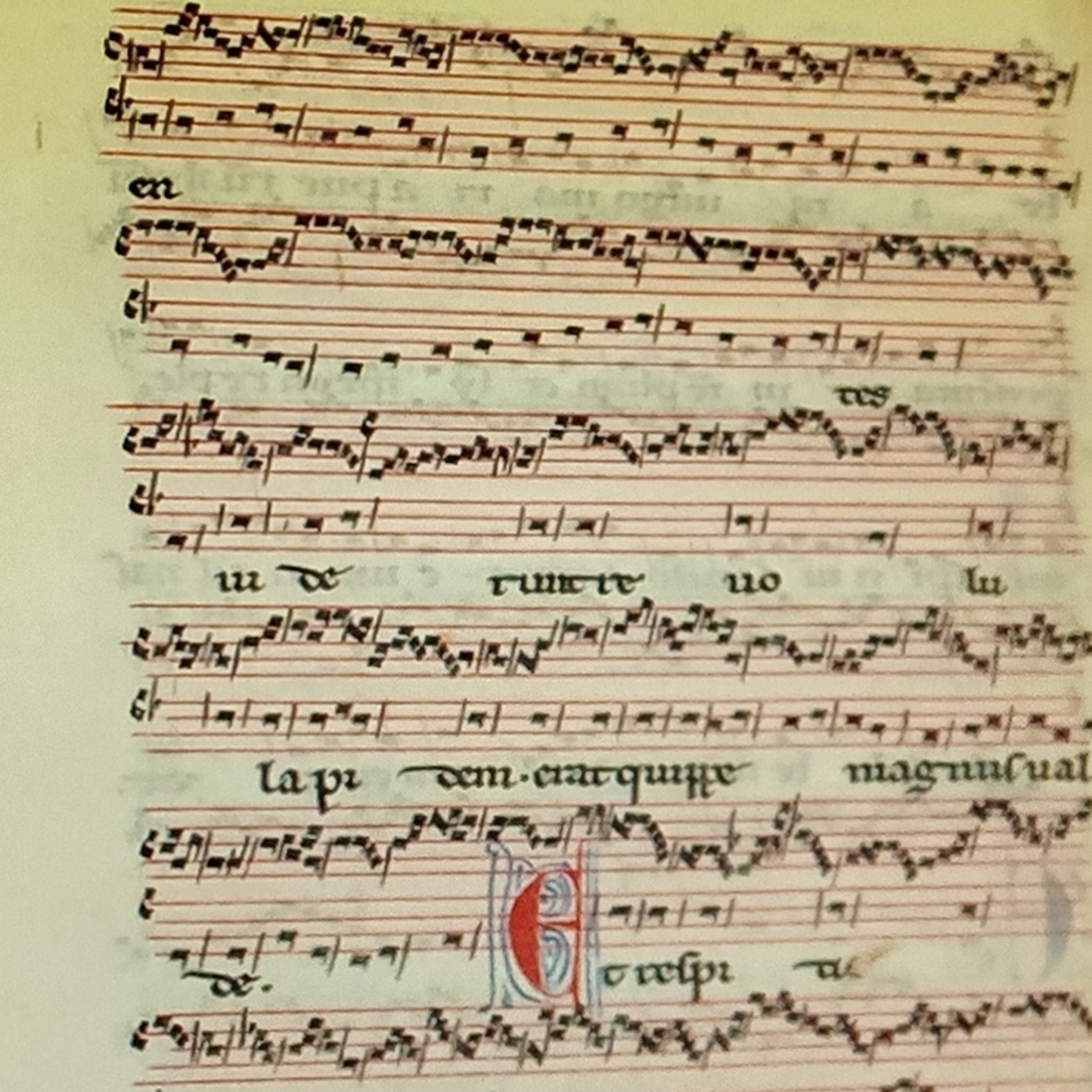

Today, we know that the documents, correctly dated, place the lifetime of the Organistrum between the end of 11th and the end of 12th century. In this period, musicians were experiencing new forms of polyphony as the organum sillabicum (es. Ad organum faciendum, M.17sup., Bibl.Ambrosiana, Milan), organum melismaticum or floridum (codex of Saint Martial de Limoges and Magnus liber organi de Notre Dame), the discantus, the clausula and conductus (Codex Calixtinus and Magnus liber organi de Notre Dame).

It is impossible not to wonder whether the Organistrum had any relationship with such repertoires. If it did, we must then direct our attention to finding out how, with what tuning and using what type of scale.

The first element of judgment is the definition of the area of sacred music as characteristic of all representations of the instrument.

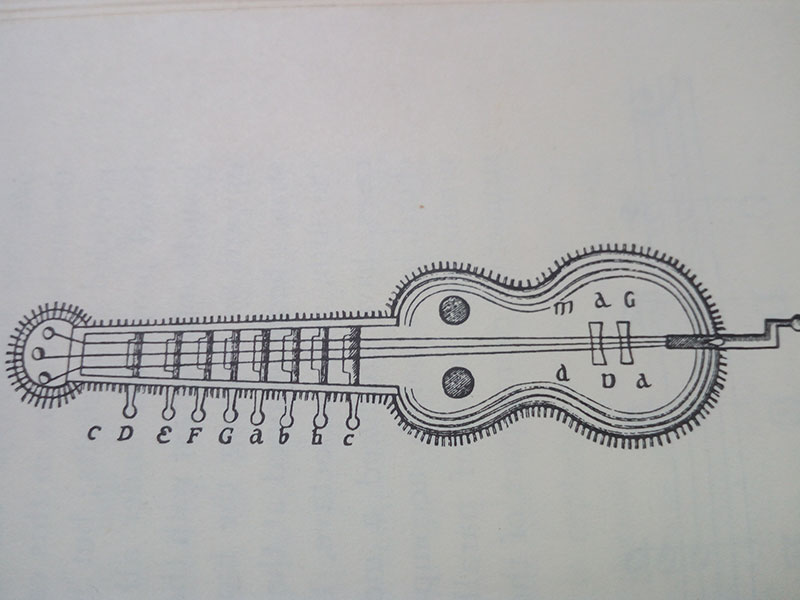

The second is the diatonic scale indicated in the precious drawing by Gerbert.

The sacred music of the time theorizes and exclusively employs the diatonic scale - this must have been the scale of any musical instrument. The series of bells and keyboards of the Romanesque organs do not, in fact, include fictae other than the Bb.

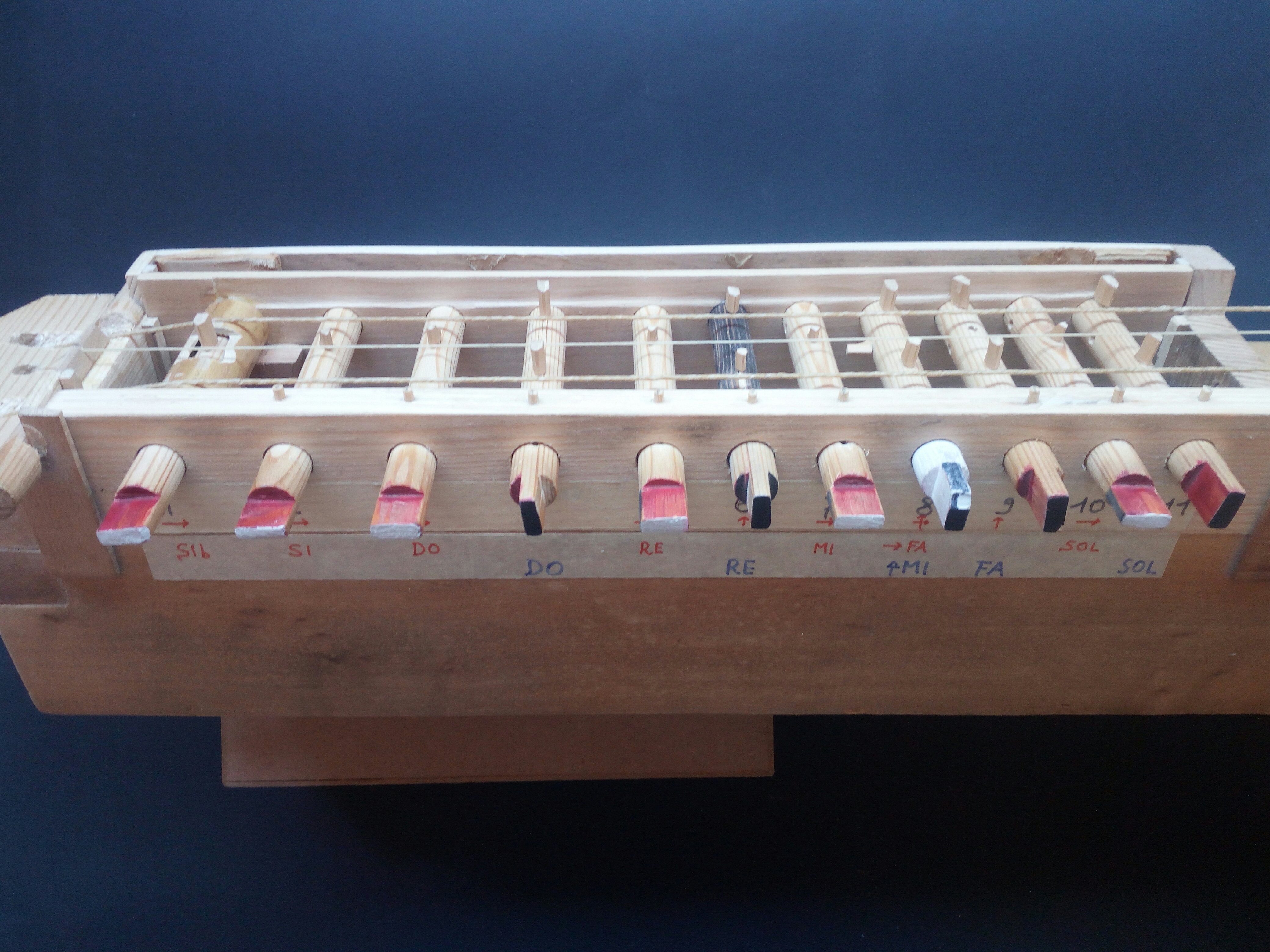

The keyboard of the Compostela instrument, with eleven keys within the half of the diapason, and therefore apparently chromatic, could probably be organized as in fig.9.

A2 --- B C3 D E F G

A3 --- Bb B C4 D E F G4

A2 --- B C3 D E F G

0 1 2 3* 4 5 6 7 8* 9 10 11

fig.9 Diatonic keyboard with 11 keys within the half of the diapason.

The nuts of the bass strings, both tuned in A2, are positioned further forward the nut of the middle string, tuned in A3, by the space of a semitone. The keys have hurdy-gurdy-like separate tangents and have vertical movement. Keys 4, 6, 9, 11 touch only the outer strings to play the notes of the lower octave. Key 1 acts on the central treble string passing under the nuts of the lateral strings. Keys 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 and 10 touch the treble string to play the notes of the highest octave. Keys 3 and 8 are the only ones enabled to act alternatively on the central string or on the side ones, after 90° rotation of the bar (fig.10).

The scale starts from A2, and not from C3 as in Gerbert, because A2 is the lowest note of the repertoire (cod. Pluteus, c.LXX r.), as can be seen from the analysis of the parts of tenor of the melismatic Organa in Magnus Liber Organi de Notre Dame. The tenor part’s highest note is generally D4, and only in very rare cases F4 (code Pluteus, c.LXVII r. And LXXXIIII, r./v.), while A4 appears only in non-melismatic compositions (code Pluteus, LXXXVIII r.).

In the first octave the Bb is missing, though this note is not foreseen in the Guidonian Gamut and consequently is not used in this repertoire. The natural B of the same octave is found, at least to my knowledge, only in one case (cod. Pluteus, c. CXXII).

To play the notes of the first octave, the player who turns the crank keeps the middle string away from the edge of the wheel. To continue on to the second octave, he moves the side strings away. All this to avoid using the Organistrum as a drone instrument, limited to only two modes at a time, in a style appropriate for secular and folk music performances.

Using the same string selection system, the compass from A2 to F4 - and up to A4 - can also be obtained with the 8 key diatonic keyboard, having the foresight to tune two strings in A2 and the third one an octave higher. (In this case, however, the position of the sib would necessarily be at the beginning of the row and not, as in Gerbert's keyboard, at the end).

Should this system look too complicate we can imagine a shorter diatonic keyboard for Compostela Organistrum (long enough for playing most of the tenor parts of the repertoire) starting at A2 (all three strings), with no Bb in the first octave, reaching the eleventh key on D4 including Bb in the second octave. In this case the keys row would end visibly beyond the middle of the string (1/2 + 1/8 of diapason), the spacing of the keys couldn’t be regular as in the sculpture.

Nevertheless, no matter how structured, the diatonic keyboard of an Organistrum or a Romanesque organ could have been useful to the musician in order to check the right intervals while composing the vox organalis of organum melismaticum.

(translated from Italian)

from the book:

Giuseppe Severini

https://ojs.unito.it/index.php/archeologiesperimentali/article/view/8489

Hortus deliciarum

Hortus deliciarum Ahedo de Butron

Ahedo de Butron Boscherville

Boscherville